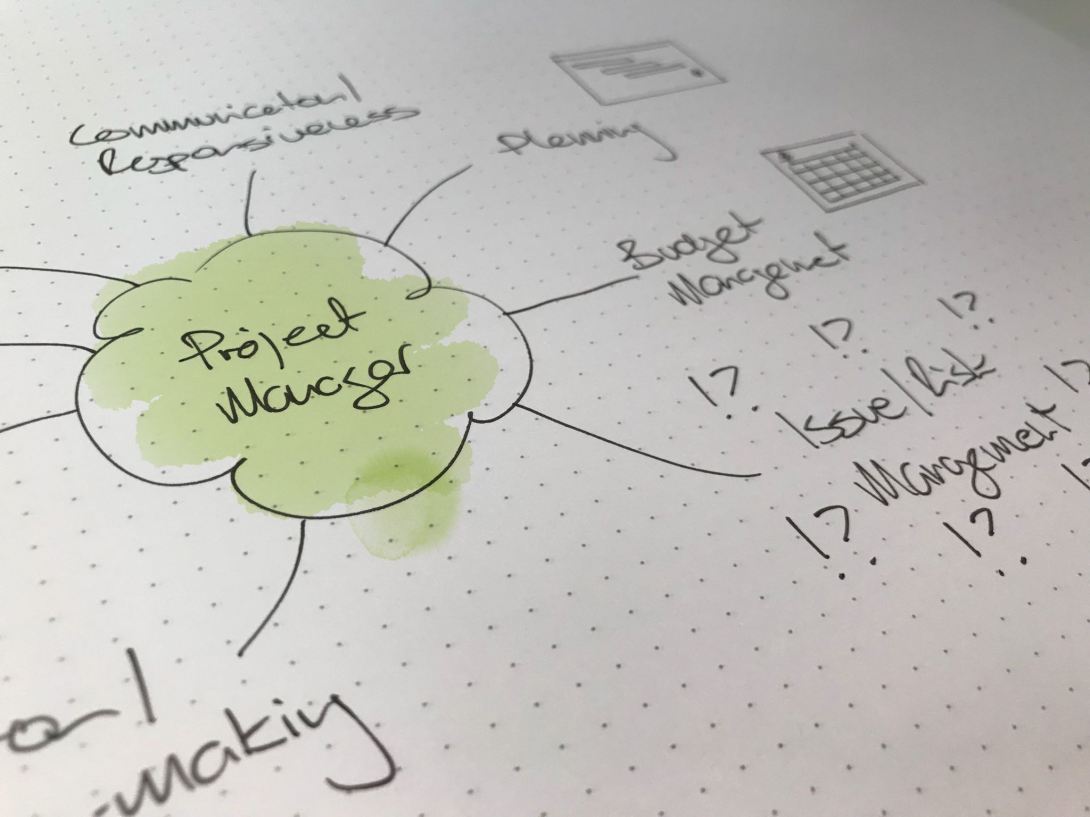

Over the past 25 years I have been fortunate to have participated in dozens of superbly managed projects (as well as one or two less well managed projects!). I have worked with good project managers and great project managers, and there is a set of attributes that all great project managers share. I want to share them with you.

Rock-solid Fundamentals

To be a great project manager you need a strong grip on the fundamentals. These fundamentals are a set of processes that manage a project’s scope, schedule, team, budget, quality, issues, risks and communications. A great project manager begins by establishing these processes – being sensitive to the project’s size and complexity – and maintains the discipline necessary to stick to them.

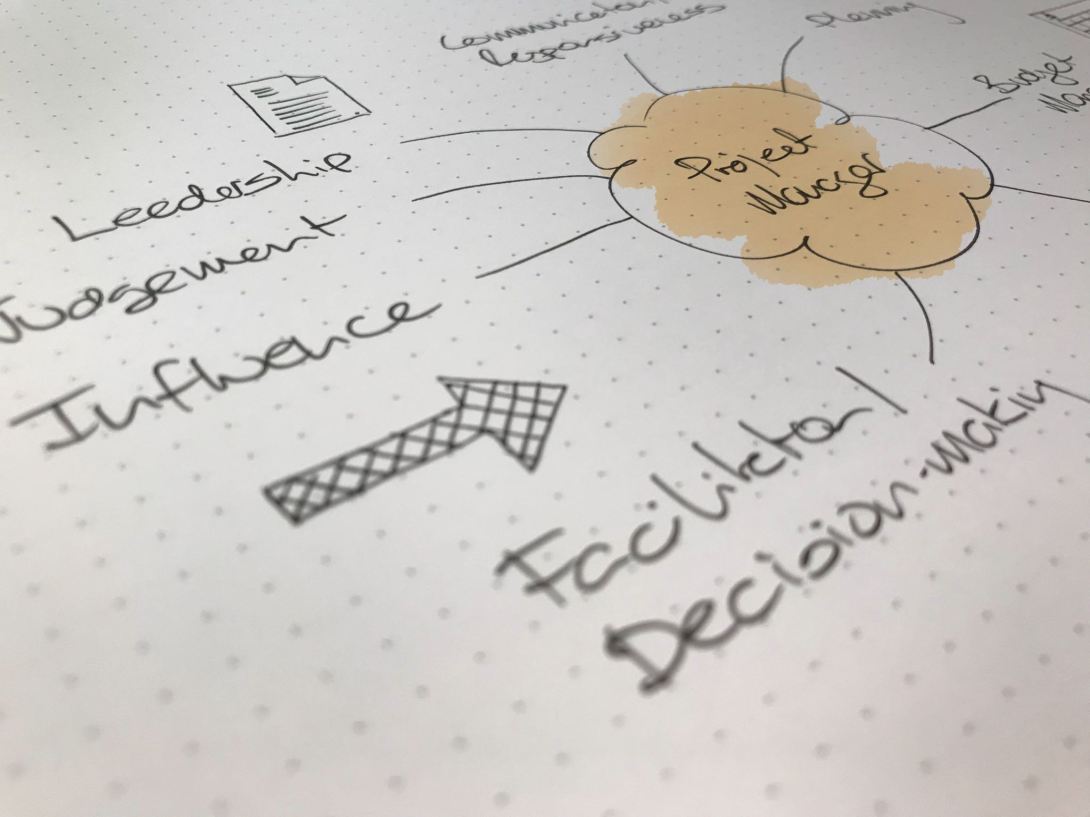

Leadership

A great project manager is a great leader. They provide a clear vision of the goal and a clear path to that goal. They sense when the team needs to heat up or cool down, and make the necessary adjustments. They act consistently and fairly at all times. They pattern the behaviours they expect in others, and hold them accountable. Finally, if they mess up they fess up, and then they move on.

Responsiveness

Great project managers always answer the mail. They provide a fast response to any question (my rule is one business day). “I’ll get back to you by Friday.” is an acceptable response. “I can’t answer, please ask Karen.” is also acceptable. The key is to never leave someone wondering if you got their message or if you care about their problem. Problems don’t age well.

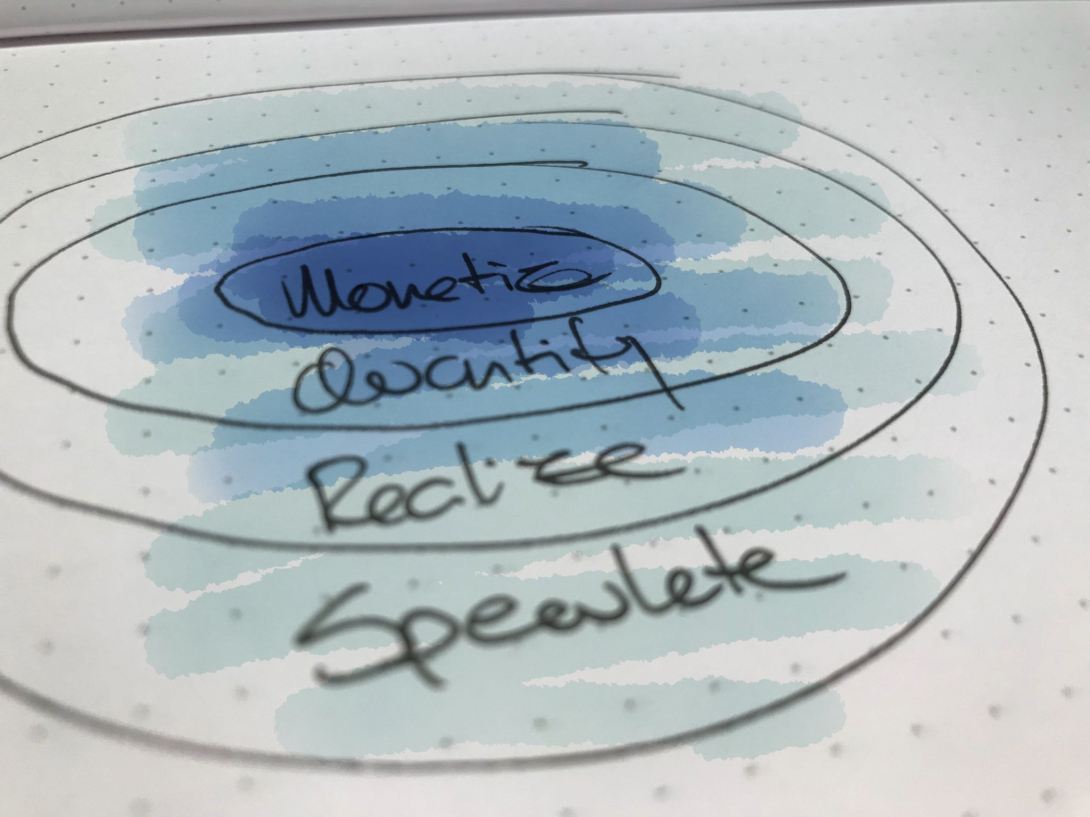

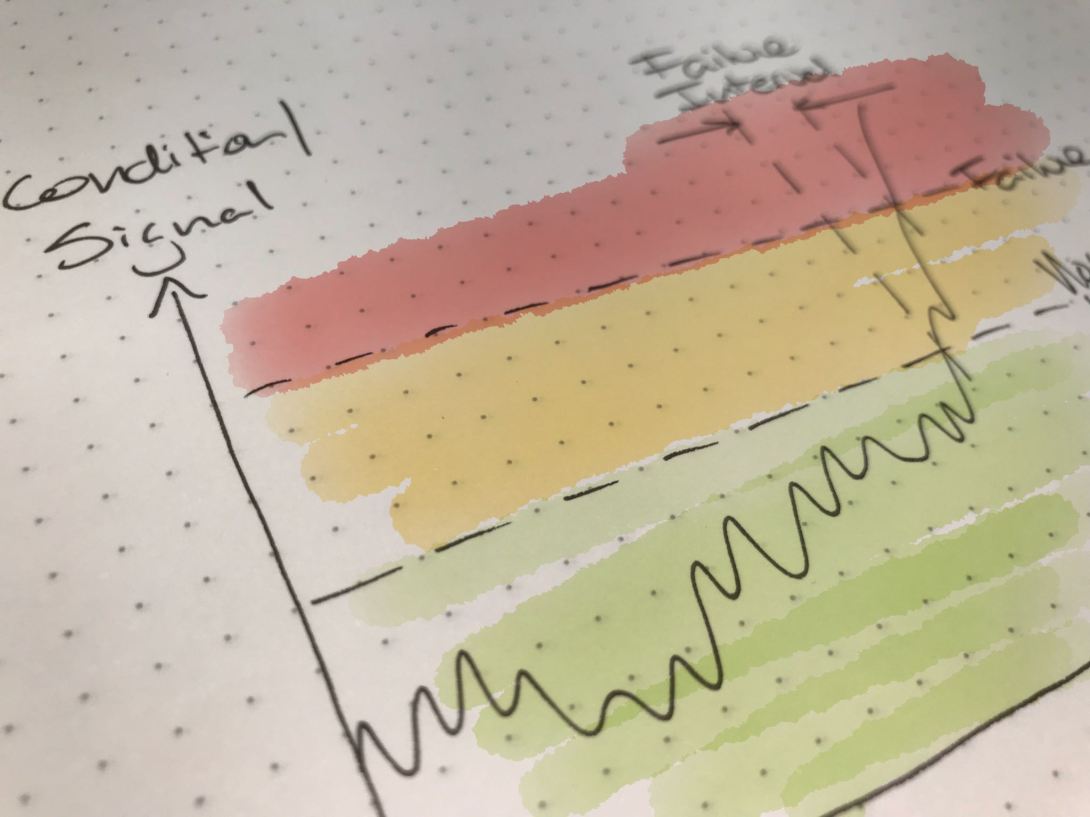

Anticipation and Judgement

A great project manager continuously and realistically assesses current project conditions across a broad range: technical issues, customer satisfaction, team performance and so on. They know who to consult, and when. They use both their head and their gut to see problems before they occur (if you have been doing the job for 20 years you should feel when something is wrong). They take timely and measured action – at the very least go find out if their gut-feel is right. They don’t over react. They make decisions in a timely manner: sometimes rapidly, sometimes gradually.

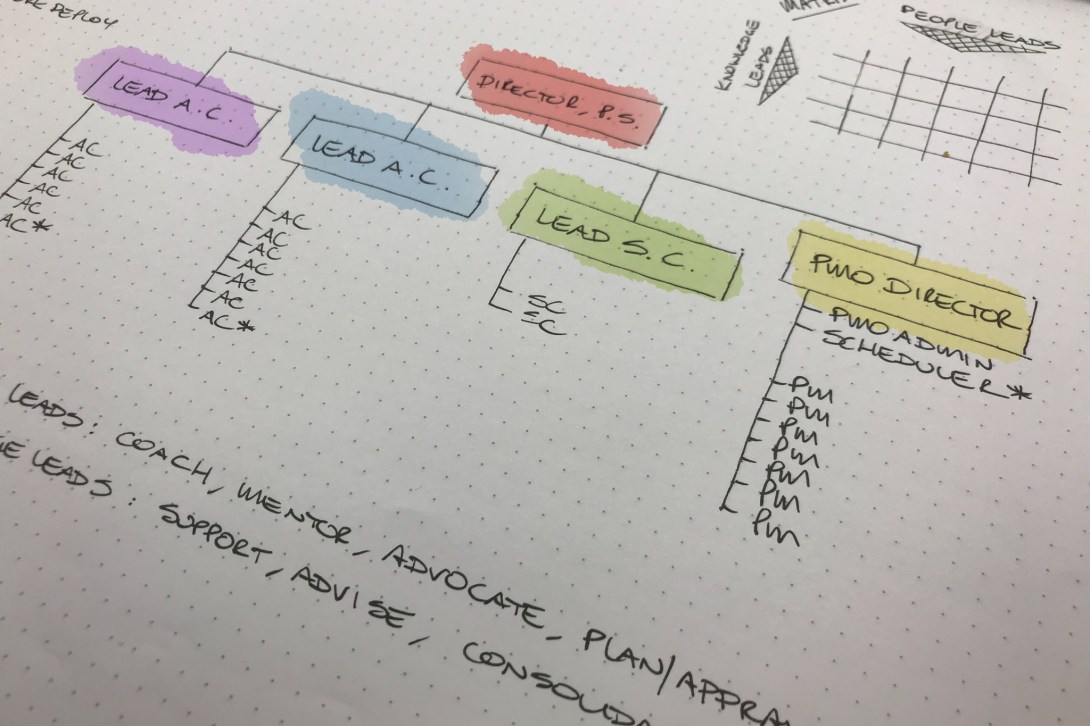

Organizational Awareness and Influence

Great project managers can shape opinion. They are always well prepared and articulate. They build relationships before there is an issue, not once there is an issue. They pick their battles, asking two questions: do they care enough to fight for a particular outcome, and can they win if they do fight? A great manager understands the personality type of all key stakeholders, knows who has power, and understands what their objectives are.

Communication

To be a great project manager you must be a great communicator. Great managers understand that it is the responsibility of the communicator to confirm that the communicatee is receiving the message and understanding it. They don’t just issue communications, they consult and confirm to ensure that their message has achieved the intended result. They also know when to include someone in the conversation, and when not to.

Facilitation and Decision-making

Finally, the great project managers help the team to clarify issues or ideas. If a technical person and a business person are not understanding each other, then the project manager translates for them. They help people make decisions by providing a process for decision-making that:

- Asks clarifying questions like “what problem are we trying to solve”;

- Assesses all the options (and remember that doing nothing is always an option);

- Identifies the option that best meets the objectives;

- Helps everyone buy into the decision (e.g., make sure everyone is heard); and

- Records the decision so that we don’t forget and make the decision again later.

They also know when to step in and just make the call. No analysis paralysis.

These are the hallmarks of great project managers. They are not what great managers do, they are ways in which they get things done. Seven habits that separate the good from the great.